In this post I will focus on the structure of trak boxes in mp4 with of a focus on using them to describe video telemetry.

To understant the moov boxes introduced last week, you must first know a bit more about the media binary written into the mdat box.

Jumping into mdat binaries

In addition to the video and audio captured by the cameras lens(es) and microphone(s), the cameras sensors (GPS, IMU, etc) are recording many measurements per second.

As data is being generated it is being stored (because a camera has limited memory). The camera firmware is built to be efficient and write data to the file quickly, the decoding and understanding of the data can be understood later.

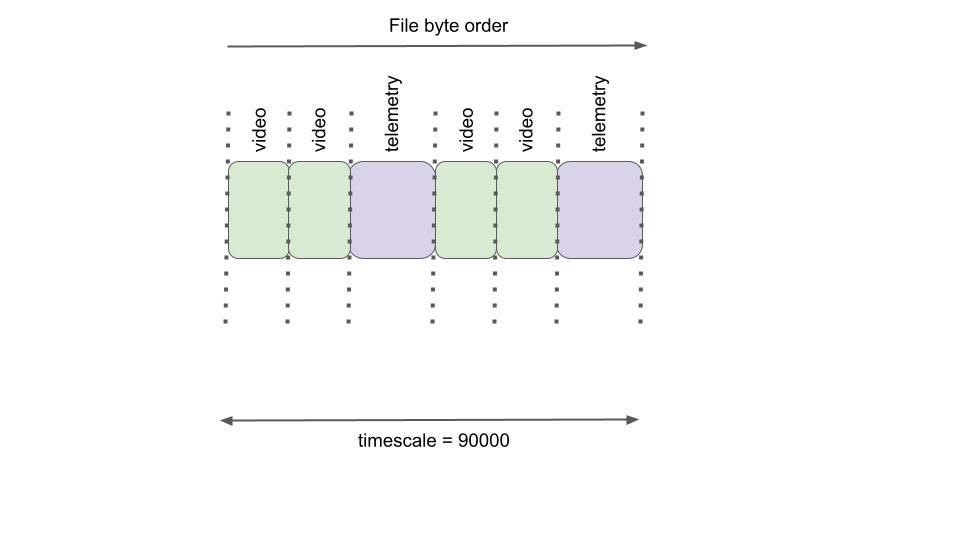

If you think of a single binary file, this means the camera is generating a mix of video, audio, and telemetry and writing it all to a single binary as time progresses. Once the recording has finished you are left with a binary containing bytes of video, audio and telemetry data all interleaved (that is impossible to understand as a human reading it).

For example;

24 bytes of video

16 bytes of audio

8 bytes of telemetry

8 bytes of telemetry

16 bytes of telemetry

16 bytes of telemetry

24 bytes of audio

16 bytes of video

...

The above sample is completely made up. I am simply trying to highlight the “visual messiness” of this binary file. For example, below is a CAMM case 5 sample containing 28 bytes of telemetry.

\x00\x00\x05\x00\x19\xf9a)7\xacI@\x02\xd4\xd4\xb2\xb5~\xf5\xbf33333\x03g@

It probably won’t make any sense (yet) but imagine the mdat being a document with many binary samples like this for video, audio, and telemetry (and possible other things too) all mixed together in one big document.

The understanding of where everything lives in this file (mix) is handled in the moov box traks. The video trak tells decoders where the video bytes are (and their time in relation to the video), the audio trak tells decoders where/when the audio bytes are, and yes, the telemetry trak tells decoders where/when the telemetry bytes are.

Jumping into moov binaries

Below is an illustration of the box structure of a video file with CAMM telemetry.

mpeg4 [154972743]

├── b'ftyp' [8, 16]

├── b'mdat' [16, 154967524]

└── b'moov' [8, 5171]

├── b'mvhd' [8, 100]

├── b'meta' [8, 111]

├── b'trak' [8, 2565]

│ ├── b'tkhd' [8, 84]

│ └── b'mdia' [8, 2465]

│ ├── b'mdhd' [8, 24]

│ ├── b'hdlr' [8, 36]

│ └── b'minf' [8, 2381]

│ ├── b'nmhd' [8, 4]

│ ├── b'dinf' [8, 28]

│ └── b'stbl' [8, 2325]

│ ├── b'stsd' [8, 33]

│ │ └── b'camm' [8, 17]

│ ├── b'stts' [8, 1352]

│ ├── b'stsz' [8, 724]

│ ├── b'stsc' [8, 80]

│ └── b'co64' [8, 96]

I’ve already explained the mdat is a single binary stream. The moov data is written as binary, however in a more structured in a way that allows for easier identification of the child boxes that can be present as per the mp4 specification.

Lets start with the moov box which can contain a number of data elements. For the purpose of telemetry we only need to set the following data elements for this container box:

- size: how many bytes the

moovcontainer box contains (this is the sum of all bytes for the child boxes within it – above that’s5171) - type: always

moov

So writing the structure of the moov container box you have; size + type which we can encode in binary.

Once this is written we can write the next box – mvhd. Once we define the mvhd contents (the data elements) and encode as binary we can append to the end of the moov binary already written.

We start to get a binary file with a structure that is structured;

moov box binary

mvhd box binary

meta box binary

trak box binary (for telemetry)

tkhd box binary

mdia box binary

...

trak box binary (for video)

...

When the entire telemetry moov container is decoded, the type fields (that all conform to mp4 spec) can be easily located and the data they contain read as defined. For example, the trak container box for telemetry can be located, and the start and end of the nested boxes in the binary can be identified using the size property (for example, I know the trak box containing CAMM metadata is exactly 2565 in total when all nested boxes are added up). This sizing information makes it easy to understand for decoders to decipher the nested structure.

To illustrate the telemetry trak boxes that are used specifically for telemetry we can start by comparing our GPMF and CAMM trak boxes using the Telemetry Injector script (print_video_atoms_overview.py)

GPMF;

python3 print_video_atoms_overview.py GS018423.mp4

└── b'trak' [8, 574]

├── b'tkhd' [8, 84]

├── b'mdia' [8, 438]

│ ├── b'mdhd' [8, 24]

│ ├── b'hdlr' [8, 34]

│ └── b'minf' [8, 356]

│ ├── b'gmhd' [8, 24]

│ ├── b'dinf' [8, 28]

│ └── b'stbl' [8, 280]

│ ├── b'stsd' [8, 24]

│ │ └── b'gpmd' [8, 8]

│ ├── b'stsz' [8, 88]

│ ├── b'stsc' [8, 20]

│ ├── b'stco' [8, 84]

│ └── b'stts' [8, 24]

└── b'edts' [8, 28]

CAMM;

python3 print_video_atoms_overview.py 200619_161801314.mp4

├── b'trak' [8, 2565]

│ ├── b'tkhd' [8, 84]

│ └── b'mdia' [8, 2465]

│ ├── b'mdhd' [8, 24]

│ ├── b'hdlr' [8, 36]

│ └── b'minf' [8, 2381]

│ ├── b'nmhd' [8, 4]

│ ├── b'dinf' [8, 28]

│ └── b'stbl' [8, 2325]

│ ├── b'stsd' [8, 33]

│ │ └── b'camm' [8, 17]

│ ├── b'stts' [8, 1352]

│ ├── b'stsz' [8, 724]

│ ├── b'stsc' [8, 80]

│ └── b'co64' [8, 96]

As you can see, the box structure and types are almost identical between the GPMF and CAMM video. What I am trying to illustrate here is that the boxes and their structure are defined in the mp4 specification (and not unique to a specific telemetry type). This means any decoder can read the contents of a box and get the data within it (whether it knows how to interpret it or not).

Though before we can start writing all the boxes in the telemetry trak we first we need to actually define the crucial data that is held in these nested boxes to define the telemetry.

I’ve briefly explained some of the boxes in the moov container box, and will gloss over many in this post to focus on those that are most critical in describing how the telemetry in mdat is deciphered. I will come back to the other boxes, like hdlr, when we talk about specific telemetry types.

I’m also going to gloss over the entirety of the contents of each box (that needs to be written as binary) for now and just explain the most important data elements for this explanation (those nested in the stbl (sample table) box).

Next week, when we start writing this data to binary in more detail, I will explain more, promise.

Let’s start with the stsd (sample description) box.

stsd

The sample description box stores information that allows readers to decode samples in the media. In the case of our telemetry (GPMF and CAMM), there is where a structured description of the table is held.

The box itself contains the following elements;

The exact format of the sample description table data element varies by media type. That is, in our case the stsd will differ depending on the standard, either GPMF or CAMM. You can see this clearly as for each telemetry type, the stsd container box contains two different nested boxes.

The sample description table data element is fairly simple in terms of the data it contains. The video sample description contains information that defines how to interpret video media data.

The table has four columns; size, data format, format reserved data, and data reference index (this last column is used later by the stsc box).

In the telemetry example the sample description can be be very simple;

17,camm,0,1

Above the size of the description (row) is 33 bytes, the data format is camm, the format reserved data is 0 (which is always the case), the reference ID is 1 (you’ll see me use this ID in the stsc box later).

You will also notice that the stsd box has a nested box, either camm or gpmf depending on the datatype.

│ ├── b'stsd' [8, 33]

│ │ └── b'camm' [8, 17]

and

│ ├── b'stsd' [8, 24]

│ │ └── b'gpmd' [8, 8]

Where these boxes come from is described here;

These four fields (of the sample description table) may be followed by additional data specific to the media type and data format.

In some camm videos I’ve seen this data contain, application/gyro\x00, e.g

17,camm,0,1,application/gyro\x00

…but it’s not actually nessasary.

The box name camm is inherited from the data format column in the sample description table. As long as the data format column is set to camm (or gpmf), the camm box will appear like this in a nested structure.

If you’re wondering why this section doesn’t define the CAMM cases (or GPMF data types), that’s because that’s done in the binary.

If this is still unclear, in the next weeks I will walk through a real life example demonstrating everything needed to write valid telemetry into a video.

stco (used by gpmf) / co64 (used by camm) (chunk offset box)

In the case of telemetry data samples, the offset in bytes to each telemetry sample reported in mdat binary. As noted, the mdat binary has a mix of many data types, and this offset accounts for these values too (but only reports the offset for telemetry points).

Take my example used early,

24 bytes of video

16 bytes of audio

8 bytes of telemetry

Here the offset for the first telemetry entry is 40 bytes into the mdat.

The offset to the first video entry is 0 bytes and offset to the first audio entry is 24 bytes. However, the telemetry trak doesn’t care about this information. This is the job of the video and audio traks.

The box itself contains the following elements;

Here, the chunk offset table is where the key information about the telemetry data is held.

The chunk offset table keeps a track of the offset each telemetry sample in a table with a single column, where each row entry represents the offset in bytes of a telemetry sample.

For example if the table looked like this;

40

48

56

96

Here the offset for the first telemetry entry is 40 bytes into the mdat, the second is at 48 bytes, the third at 56 bytes, and the fourth sample can be found after 96 bytes.

A note on co64

In CAMM telemetry the sample table atom contains 64-bit chunk offset boxes. The stco only allows for 32-bit offsets (which GPMF produces), hence the co64 box is used in CAMM. The actual structure of the chunk offset table is identical.

stsz (sample size box)

In each telemetry specification (camm/gmpd) samples represent a measurement (more details on how these look later). Telemetry samples can be different sizes (in bytes). For example, a GPS sample will be a different size to an accelerometer sample because the amount of data being stored is different. This box tracks the size of each reported sample.

The box itself contains the following elements;

The key one being the sample size table (the other elements are really information about the box itself).

The sample size table keeps a track of the size each telemetry sample in a table with a single column, where each row entry represents the size in bytes of a telemetry sample reported. For example if the table looked like this;

28

28

28

28

Would mean that the first telemetry sample is 28 bytes, the second sample is 28 bytes, the third sample is 28 bytes, and the fourth is 28 bytes. Though remember, these samples could be different sizes if they are reporting different telemetry (e.g. gps and accelerometer readings).

stts (time to sample box)

This box stores duration information for the samples, providing a mapping from a time to the corresponding telemetry data sample mdat. This is needed because stco has no concept of time (bytes into a file have no concept of time), hence, players (and software reading the telemetry) needs this data to know the actual time point in the video the specified point is found.

The box itself contains the following elements;

The time-to-sample table contains two columns. Sample count and sample duration for each telemetry point. Here’s an example;

5,18000

It’s first important to point out sample duration is not related to something called time scale defined in the telemetry trak in the media header box (trak > mdia > mdhd).

This box contains a few variables, but we are most interested here is the time scale value;

A time value that indicates the time scale for this media—that is, the number of time units that pass per second in its time coordinate system.

For example, if we set a time scale = 90000, that means one second = 90000 units. The 90000 could be any number you want (with the caveat it must be divisible by number of sample reported per second). For example, if we had 5 samples per second (reported every 0.2 seconds), 90000/5 = 18000, which mean measurement 1 is at 0 timescale, measurement 2 at 18000, measurement 3 at 36000 … measurement 5 at 72000.

Now back to our example. We have sample count = 5, and sample duration = 18000. This means we have 5 consecutive samples, each measuring 18000 seconds (this saves us having to write one sample per table row, taking up space, when the duration of each sample are all the same, which is quite often the way sensors report data).

Let me show you an expanded example now representing 11 telemetry samples in the time-to-sample table;

5,18000

1,90000

5,18000

Here the first 5 samples are all 18000 long, the sixth is 90000 long, and the final 5 sample are all 18000 long.

stsc (sample to chunk box)

As telemetry samples are recorded, they can be collected into chunks. Chunks allow for data optimisation. One chunk can represent one sample (least efficient), or one chunk could represent many samples (more efficient). This box tracks how many samples are recorded in each chunk.

A good example of this is CAMM telemetry where we can have samples reported from GPS, accelerometers, magnetometers, etc all at different rates. It is therefore often more efficient to group these as chunks.

The box itself contains the following elements;

The sample to chunk table (the data element in this box where chunk information is held) has 3 columns; first chunk, samples per chunk, sample description IDs.

The sample description IDs referenced are contained in the stsd box (in the sample description tables data reference index column, mentioned earlier in this post). I will cover this in a later post.

A simple stsc table might contain the following values;

1,1,1

2,1,2

This references two chunks.

Chunk 1 has 1 sample in it, and the sample is described in the stsd under description ID 1.

Chunk 2 has 1 sample in it, and the sample is described in the stsd under description ID 2.

Turning this to a real example, this could be CAMM telemetry whereby the first chunk is reporting a single sample of GPS data (defined in description ID 1) and the second chunk is reporting a single sample of accelerometer data (defined in description ID 2).

The table can get more complex.

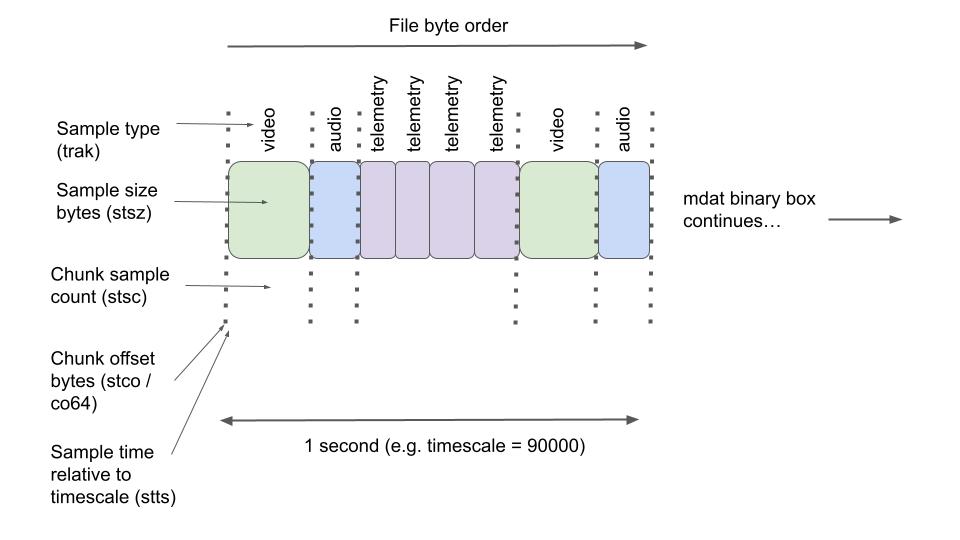

This table illustrates the sample to chunk table for the chunk example shown in the image above (with 5 chunks).

At first it might be confusing why only chunks 1, 3, and 5 are reported. This is because each table entry corresponds to a set of consecutive chunks, each of which contains the same number of samples.

Chunk 1 and 2 contain the same amount of samples and the same type of samples (ID 23). Chunks 3 and 4 contain the same samples (ID 23), but only one sample is reported in the chunk, hence the need for a new row in the table. The fifth chunk contains a different type of sample (ID 25), hence the need for a new entry in the table for this entry too.

If all the chunks contained the same amount of samples and contained the same type of samples (by ID), then this table would only be one row.

Mapping these boxes to mdat

So far this explanation has been fairly abstract. Let me fix that and jump into some examples to demonstrate.

For reference, here’s a reminder how these boxes map against the data held in the mdat binary;

Example 1.0

Here is a made up example of data for video and telemetry samples inside a mdat binary representing 1 second (in our telemetry this is a timescale of 90000, defined in the mdhd box).

\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00

\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00

\x00\x00\x05\x00\x19\xf9a)7\xacI@\x02\xd4\xd4\xb2\xb5~\xf5\xbf33333\x03g@

\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00

\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00

\x00\x00\x05\x00\x86\x92\xc9\xa9\x9d\xadI@\x9a\x99\x99\x99\x99\x99\xf5\xbf\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x80f@

Each line of the binary is a sample of either video or telemetry data. Each line is also chunk. Therefore each chunk contains one sample.

Let me draw this out visually, in case it proves helpful;

The first telemetry sample looks like this;

\x00\x00\x05\x00\x19\xf9a)7\xacI@\x02\xd4\xd4\xb2\xb5~\xf5\xbf33333\x03g@

And second like this;

\x00\x00\x05\x00\x86\x92\xc9\xa9\x9d\xadI@\x9a\x99\x99\x99\x99\x99\xf5\xbf\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x80f@

Each telemetry sample is 24 bytes (3 double values of 8 bytes + 4 byte header).

For reference, decoded this reports CAMM case 5 samples with the following values;

{"latitude": 51.3454334, "longitude": -1.343435, "altitude": 184.1}

{"latitude": 51.356374, "longitude": -1.35, "altitude": 180.0}

If you’re curious to see how I converted these to binary see this script. I will also explain in much more detail next week.

co64 (not stco because CAMM type)

So the first chunk of video binary is (which is 4 bytes);

\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00

But in the telemetry trak, we don’t need to worry about this. That’s handled by the boxes (stsz, etc) in the video trak.

However it is still important because we do need to count the number of bytes until we reach the first telemetry sample which in this case is 4 bytes (first chunk of video) + 4 bytes (second chunk of video) = 8 bytes.

Therefore in our telemetry trak, the first stco chunk offset table row value is 8.

Before the second telemetry point is 2 more video samples (each of 8 bytes), so this means the total offset to the second piece of telemetry is; 4 (preceding chunks of video) * 4 bytes (each chunk size) + 28 bytes (1st telemetry sample) = 44 bytes .

This gives a telemetry stco chunk offset table for this binary as follows;

8

44

stsc

We’ve decided that one chunk of telemetry contains one sample. The telemetry samples also all report the same type of data (CAMM case 5).

So the sample to chunk table for my telemetry looks like this;

1,1,1

Written in words; all chunks of telemetry from chunk 1 onwards all contain 1 telemetry sample which matches the description ID 1 (found in the stsd box).

stsz

We also need to know the sample size (in bytes).

In this case latitude, longitude and altitude are all is required to be doubles (which are each 8 bytes). So 3 * 8 = 24. The sample also needs a header (which is always 4 bytes). All our telemetry samples are therefore 28 bytes (they are all the same because both of the two points are reporting the same data type – CAMM case 5).

The sample size table would therefore be;

28

28

stts

Now all we need to know is the relative video time (stts) this sample represents – put another way, in playback, how many seconds into the video this sample occurs.

As noted, in our sample only two telemetry measurements are reported per second. Thus we know the values for stts (assuming timescale in mdhd is defined as 90000) are 45000 apart giving us a time-to-sample table as follows;

2,45000

Example 1.5

Let’s assume the video from example 1.0 continues in the same pattern for another second.

The boxes would now contain data as follows;

co64

Chunk offset table;

8

44

80

116

Before the third telemetry point is 2 more video samples (each of 4 bytes). So we get 44 + 28 (2nd telemetry sample) + 4 (5th video sample) + 4 (6th video sample) = 80 offset. Then the same pattern again, 80 + 28 + 4 + 4 = 116.

stsc

Sample-to chunk table;

1,1,1

No change, because each chunk still contains one sample, of description ID 1.

stsz

The sample size table need the two other telemetry byte sizes reported (each 28 bytes as they are the same data type);

28

28

28

28

stts

And finally the time-to-sample table needs the additional 2 points of telemetry (each with spacing 45000) reported;

4,45000

More examples

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but most telemetry, including GPMF and CAMM is not typically stored as simply as shown in example one, but hopefully you’re getting the idea of things.

Take CAMM for example. CAMM not only reports GPS data (as shown in example one). It can also be used to report acceleration, roll, etc in different samples (1 sample for GPS, 1 sample for acceleration, etc). Each of these samples are reported at different frequencies (rates). For example GPS might be reported 10 times a second, whilst acceleration might be reported 100 times per second. Each sample type from each sensor is a different size.

Similarly, its not always a fixed frequency that a sensor will report data. For example, a GPS chip might report up to 16 measurements a second. Up to being the key words. In poor conditions where the GPS satellites are out of view, significantly fewer (or even no) measurements might be reported.

In short, this adds a lot more variance to sample sizes value (in stsz), the time of each sample (stts) and the offsets (stco) – and this is where having multiple samples per chunk becomes very useful (stsc).

I briefly talked about writing the data into binary this week. In the next post I will put theory into practice and walk-through writing both telemetry binary into the mdat box and the required metadata into the moov box in the CAMM standard.

A special thanks to…

…the Apple team who wrote a brilliant overview to video files atoms (boxes) here that significantly helped me understand the topic and write this post.

We're building a Street View alternative for explorers

If you'd like to be the first to receive monthly updates about the project, subscribe to our newsletter...