Learn how GPS works and why some receivers are more accurate than others.

At any given time, there are at least 24 active satellites orbiting over 12,000 miles above earth.

These satellites are owned by the United States government and operated by the United States Space Force. They power the Global Positioning System (GPS).

The positions of the satellites are constructed in a way that the sky above your location will always contain at most 12 satellites.

The primary purpose of the 12 visible satellites is to transmit information back to earth over radio frequency (ranging from 1.1 to 1.5 GHz).

The data sent down to earth from each satellite contains a few different pieces of information that allows a GPS receiver to accurately calculate its position and time.

A GPS receiver is a device that can listen for (using an antenna), understand, and process the information transmitted by the satellite. Almost all modern smartphones contain GPS receivers.

An important piece of equipment on each GPS satellite is an extremely accurate atomic clock. The time on the atomic clock is sent down to earth along with the satellite’s orbital position and arrival times at different points in the sky. In other words, the GPS module receives a timestamp from each of the visible satellites, along with data on where in the sky each one is located (among other pieces of data). This data is known as the GPS almanac.

If the GPS receiver’s antenna can see at least 4 satellites, it can accurately calculate its position and time using the GPS almanac data received. This is also called a lock or a fix. When you first turn on a GPS receiver (like your camera), it can take a few minutes for it to lock onto 4 satellites.

Nearly all GPS receivers convert the GPS almanac to NMEA data output. The NMEA standard is formatted in lines of data called sentences. Each sentence contains various bits of data organised in comma delimited format. Here’s example NMEA sentences from a GPS receiver with satellite lock (4+ satellites, accurate position):

$GPRMC,235316.000,A,4003.9040,N,10512.5792,W,0.09,144.75,141112,,*19

$GPGGA,235317.000,4003.9039,N,10512.5793,W,1,08,1.6,1577.9,M,-20.7,M,,0000*5F

$GPGSA,A,3,22,18,21,06,03,09,24,15,,,,,2.5,1.6,1.9*3E

For example, the GPGGA sentence contains the follow:

- Time: 235317.000 is 23:53 and 17.000 seconds in Greenwich mean time

- Longitude: 4003.9040,N is latitude in degrees.decimal minutes, north

- Latitude: 10512.5792,W is longitude in degrees.decimal minutes, west

- Number of satellites seen: 08

- Altitude: 1577 metres

Although it is technically possible to get a position from less than four satellites, the margin of error of this position can be rather large. As such, most devices are programmed to start reporting data after locking onto at least four satellites.

GPS Positional Accuracy

GPS-enabled smartphones are typically accurate to within a 5m radius under open skies.

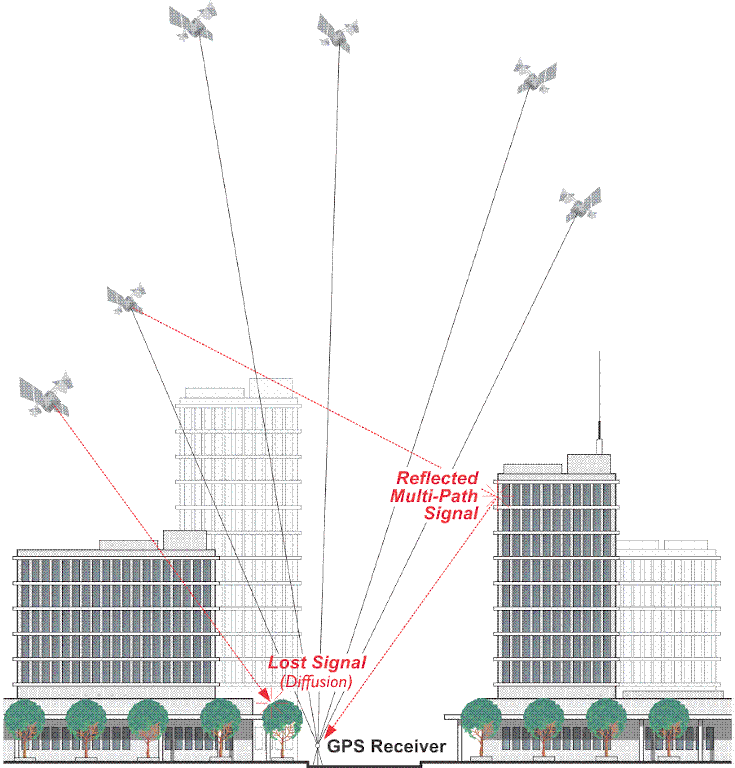

GPS Accuracy depends on a number of variables; the quality of GPS receiver, signal to noise ratio (noisy reception), satellite position, environment (weather, skyline visibility, enclosed spaces, multi-path reception), obstructions such as buildings and mountains, and on smartphones the device state (low power mode, flight mode, initial fix).

It’s also worth noting almost all mobile devices process GPS at the rate of 1Hz (1 GPS measurement a second) to save power (and cost of GPS chips).

All of these factors can create errors in your reported location.

Signal noise usually creates an error from around one to ten metres.

Mountains, buildings and other things that might obstruct the path between the receiver and the satellite can cause three times as much error as signal noise.

If you’ve ever used a GPS receiver in a narrow, high-sided canyon, or in a densely wooded forest, it’s very likely you’ll have observed significant inaccuracies in the reported coordinates.

The most accurate read of your location comes when you have a clear view of a clear sky away from any obstructions and under more than four satellites.

Altitude can often appear particularly inaccurate. New GPS buyers often suspect their equipment may even be defective when they see the altitude readout at a fixed point vary by many 10’s of metres. This is normal.

With most low cost GPS receivers, the horizontal error is specified to be within about +/- 15 metres (50 feet) 95% of the time... Generally, Altitude error is specified to be 1.5 x Horizontal error specification. This means that the user of standard consumer GPS receivers should consider +/-23meters (75ft) with a DOP of 1 for 95% confidence.

To combat these errors, a couple of different assistants have been created.

AGPS (Assisted GPS) uses wireless (ground-based) networks to help relay between the satellite and the receiver when the GPS signal is weak or not able to be picked up. AGPS is mostly accomplished by GPS receivers mounted on cellular towers. When communicating with these receivers, the GPS can acquire a lock on the satellite more quickly as well as receive more accurate information. This method is what is used for GPS in mobile phones and why they’re sometimes more accurate than the GPS receivers on their own.

AGPS is most beneficial in cities where the GPS signal may have a difficult time making it through the dense maze of the buildings. In areas where there’s no mobile signal it offers little

Another method is DGPS (Differential GPS). DGPS also uses ground or fixed GPS stations to determine the location, but differs in that it finds the difference between both the satellite and the ground location reading. These ground stations may be up to 200 nautical miles from the receiver. As an example, one form of DGPS is WAAS (Wide Area Augmentation System). Originally developed by the FAA to assist aircraft GPS, WAAS uses a system of specifically built ground stations. WAAS holds a specific set of accuracy standards that ground station measurements must meet.

DGPS receivers have additional antenna that receive signals not only from satellites but directly from the ground stations. DGPS devices usually require two antennas. These are much larger and more expensive than your standard GPS device but can provide centimeter accuracy in position (it is important to note that accuracy deteriorates the further you are from the ground station). As such, DGPS units are also expensive and tend to be larger, and therefore only typically used for work where accurate location readings are important (e.g. aircrafts).

Improving GPS accuracy for outdoor 360 mapping

When it comes to capturing GPS for 360 mapping, you’re somewhat limited with regards to the improvements you can make.

You can’t cut down trees to create a clear line of site to the sky when shooting in a forest.

Checking for clear weather conditions before shooting can help improve accuracy (look for sunny, dry days).

For many tours I now also capture a secondary GPS track in addition to the data reported by the GoPro MAX’s GPS receiver as a backup.

In most areas (with a mobile signal) I’ll use my phone to do this. There are an abundance of apps that can perform GPS logging functions (search GPS logger). Ideally what you want is a tracker that will log telemetry (at a minimum; time, latitude, longitude, and altitude) to a CSV or GPX file.

I have tested the two below which, from my own usage, seem to perform well and meet the above requirements:

If your camera geo-tags photos files using the Google Street View mobile app then you will already be taking advantage your phone ability to geotag photos and won’t need to use a secondary app.

![]()

In more remote areas where I can’t rely on a mobile signal, I will bring along a standalone GPS receiver. Currently I’m using the Columbus V-1000 which has performed well to date and has very good battery life (16 hours).

When returning home, I’ll then stitch the secondary GPS track into the images using Image Geotagger, a Python script we wrote that; 1) takes a series of timestamped images, 2) a timestamped GPS track log, 3) uses linear interpolation to determine the GPS position in the track at the time the image was captured, 4) then writes the correct geo-tags into each image from the track.

We're building a Street View alternative for explorers

If you'd like to be the first to receive monthly updates about the project, subscribe to our newsletter...