How Google Maps make their satellite imagery look three-dimensional.

360 images can often look ‘flat’.

Perhaps that huge, imposing canyon that looked awe-inspiring in-person, didn’t quite turn out how you expected it in the image produced by your camera.

Usually this is down to limitations with depth perception of a camera.

If you’ve tried running with one-eye closed you’ll notice it’s harder to judge an objects distance.

Cameras suffer the same issue.

Having more than one sensor on a 360 camera helps display depth better than using a single sensor, but it’s not perfect because of the minimal overlap between images each sensor captures.

To help compensate for a cameras limitations reproducing visual depth in imagery, other techniques be employed…

Photogrammetry

Photogrammetry is the science of making measurements from photographs.

Again, the best way to visualise this is to use your eyes. Your eyeballs are using photogrammetry all the time.

You have two eyes (two sensors), processing a live feed of your surroundings. Because your eyes are slightly apart, you’re getting two different inputs at slightly different angles.

Your brain knows how far apart your eyes are, which allows it to process this info into a sense of distance by merging both feeds into a single perspective.

In the world of 360 photography, photogrammetry is used during stitching to identify control points, the same point in space in two (or more) photos. I recommend reading this post which covers control points in more detail.

Photogrammetry is often used to produce 3D surveys too. Here control points between two or more photos might be used to build a 3D model by identifying the same objects (but at different angles) in each image to model it in real space.

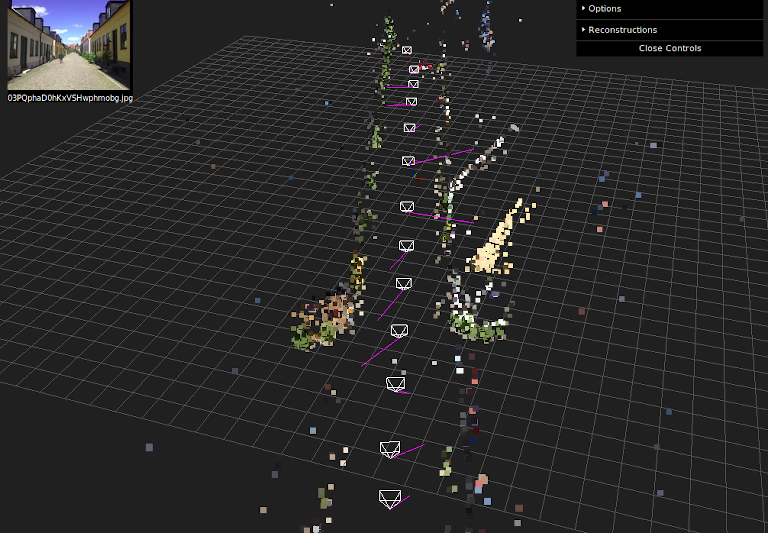

Mapillary uses photogrammetry techniques in their OpenSFM software which is implemented in the Mapillary web app when transitioning between photos (amongst other things).

OpenSfM finds the relative positions of images and creates smooth transitions between them. That process is called Structure from Motion. It works using photogrammetry by matching a few thousand points between images, and then figuring out the 3D positions of those points as well as the positions of the cameras simultaneously.

But there are limitations.

If a surface is too featureless or turbulent — like a building’s polished windows or the ocean — stitching doesn’t work very well. It’s impossible to match a feature between images if it’s there in one photo but not in the next, or if there aren’t enough hard edges or identifiable features to tell images apart.

LiDaR helps solve some of these issues.

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDaR).

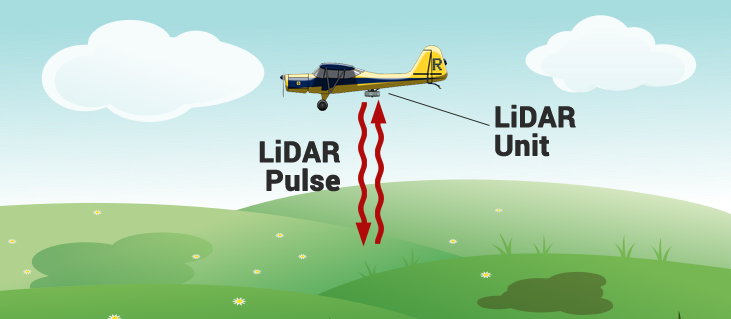

Invented in the 1960s, LiDaR stands for “light detection and ranging,” and it measures distances by sending laser pulses at a feature (a tree, the ground itself, a cliff face) and measures the reflected pulses with a sensor.

LiDaR can be likened to sonar or radar, which use sound and radio waves respectively to map surfaces and detect objects. In most cases, LiDaR uses infrared light.

Its hardware can be mounted on a plane, tripod, or automobile, as well as a drone. It’s sometimes called 3D laser scanning. Google use a pair of LiDaR scanners on their Street View cars.

LiDAR mapping uses a laser scanning system with an integrated Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) and GNSS receiver, which allows each measurement, or point in the resulting point cloud, to be geo-referenced. Each ‘point’ combines to create a 3D representation of the target object or area.

During a LiDaR survey, an active optical sensor transmits laser beams toward a target (think millions of points for top-of-the-range scanners). The laser energy is reflected by the target and is detected and analyzed by receivers in the LiDaR sensor.

The receiver records the precise time from when the laser pulse left the system to when it is returned to the sensor. Using precise pulse time, the range distance between the sensor and the target may be calculated.

LiDAR maps can be used to give positional accuracy – both absolute and relative, to allow viewers of the data to know where in the world the data was collected and how each point relates to objects terms of distance.

Engineers and earth scientists use LiDaR to accurately and precisely map and measure natural and constructed features on the earth’s surface, within buildings, underground, and in shallow water.

What is a point cloud?

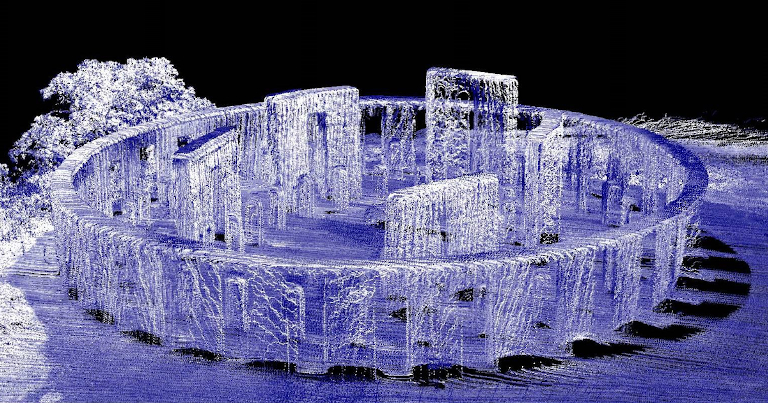

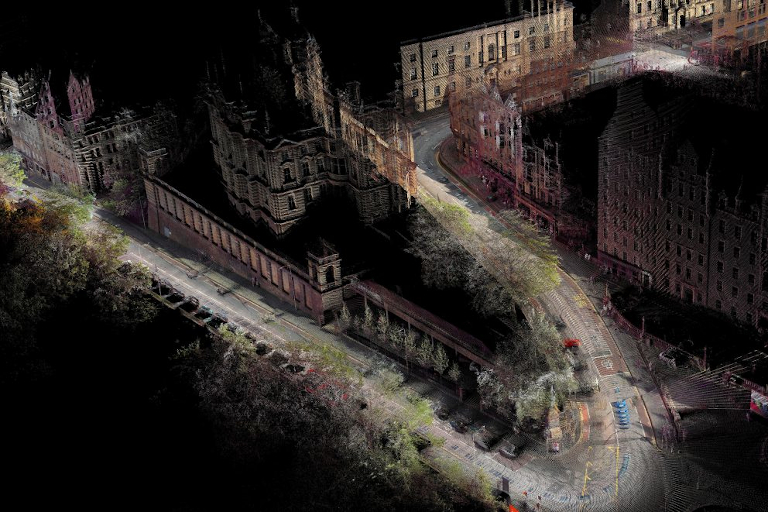

A 3D point cloud is a collection of data points analogous to the real world in three dimensions.

Each point is defined by its own position. The points can then be rendered as pixels to create a highly accurate 3D model of the object.

Point clouds can describe objects measuring just a few millimeters or objects as large as trees, and even entire forests, depending on the resolution (number of points collected) of the scanner.

Point clouds are often stylised with colour for easier analysis (using software post capture), for example, colouring the points based on their vertical height to the ground to improve the 3D visualisation.

While LiDAR is a technology for making point clouds, not all point clouds are created using LiDAR. Photogrammetry alone can be used to produce point clouds too (though when it comes to accuracy, LiDAR is hard to beat).

Mixing LiDaR sensors and image sensors

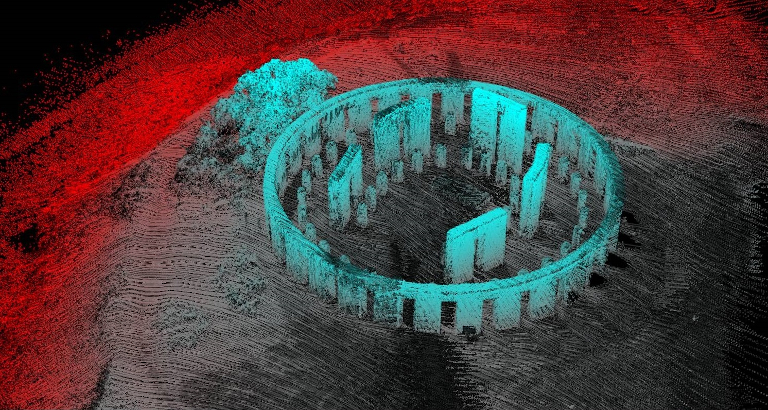

Photogrammetric point clouds have an RGB value for each point at capture.

LiDaR does not ‘see’ in colour, but points in space.

Using the two together gives a high degree of accuracy of the environment captured with the benefit of seeing it in colour (as you would with your eyes).

Placing photos on top LiDaR point clouds creates a realistic 3D render of the world, making the photo look much more realistic and life-like.

You’ve probably already seen an example of this output if you’ve ever looked at Google Maps satellite imagery.

If not, check it out for yourself.

With the cost of LiDaR having reduced significantly in recent years due to increased adoption and usage (the latest iPads include a low resolution LiDaR scanner), we don’t think it will be long until this technology is bundled into 360 cameras too…

We're building a Street View alternative for explorers

If you'd like to be the first to receive monthly updates about the project, subscribe to our newsletter...